Die Fragen, ob es unterscheidbare Lernstile gibt und ob man die Gestaltung von Lernumgebungen darauf ausrichten soll, beschäftigen nicht nur Bildungsforscher sondern auch Bildungsverantwortliche seit vielen Jahren.

Ich bin kürzlich auf zwei Beiträge gestossen, die diesen Fragen in ganz unterschiedlicher Weise nachgehen:

Carol Black, Publizistin, Dokumentar-Filmemacherin und Unterstützerin der “alternative education”-Bewegung hat einen längeren Essay zu diesem Thema publiziert: “Science / Fiction: ‘Evidence-based’ education, scientific racism & how learning styles became a myth“.

Black stellt die Diskussion um Lernstile in Zusammenhang mit grösseren gesellschaftlichen Themen (Gestaltung des Schulwesens sowie Reproduktion von Macht und Ungleichheit in einer Gesellschaft). Sie hält sich daher auch nicht lange beim Thema “auditive / visuelle / kinesthetische Lernertypen”. Dies sind wohl die am häufigsten unterschiedenen Lerner-Typen – auch wenn es für deren Relevanz im Hinblick auf Lernerfolg in für diese Typen passend gestalteten Lernumgebungen kaum belastbare empirische Forschungsbelege gibt.

***

Dazu als beispielhafter Beleg diese Aussage von Hattie / Yates:

“there is no adequate evidence base to justify incorporating learning styles assessments into general educational practice. Thus, limited education resources would better be devoted to adopting other educational practices that have strong evidence base”

(…)

“The theory that learners will learn best when their preferences are taken into account also received no serious support from the available literature on human learning. ”

(Hattie / Yates 2013: Visible learning and the science of how we learn. Routledge, p. 182-3)

***

Worum es Black geht, sind Faktionen im Wissenschaftsbetrieb, die über ihre Forschungsarbeiten ihre eigene Weltsicht zementieren wollen. Insbesondere hat sie dabei “educational conservatives” im Auge, die sie auch als “myth debunkers” bezeichnet. Black zufolge argumentieren diese so: Was in experimentellen Settings nicht als signifikant nachgewiesen werden kann, das existiert nicht.

They trumpet any research that supports their preferences and ignore or attempt to discredit any research that leans the other way. They don’t like progressive or self-directed or culturally relevant approaches to education. They don’t tend to concern themselves overmuch with less tangible aspects of children’s well-being like, say, “happiness” or “creativity” or “mental health.” They define “what works” in education in terms of test scores.

But the reality is that you can’t say ‘what works” in education until you answer the question: works for what? (…) What raises test scores may lower creativity or intrinsic motivation, and vice versa; (…) So “what the research supports” depends on what you value, what you care most about, what kind of life you want for your children. If direct instruction of kindergarteners raises early test scores but makes children anxious and unhappy, you may quite reasonably respond to the test score data by saying: who cares? Well –– the debunkers care. They care a lot. And they are dedicated to the effort to convince you that science supports their views and no others.

Black setzt diese Diskussion dann in Zusammenhang mit einer gesamtgesellschaftlichen Dimension: Von wem wird “Intelligenz” wie definiert? Welche gesellschaftlichen Gruppen verfügen über wie viel Macht und Einfluss – nicht nur, aber auch im Bildungswesen? Wie reproduzieren sich diese Gruppen?

The elephant in the room here is that the reasoning behind the ‘scientific’ claims of ‘evidence-based’ education rest on a tautological logic that was historically designed to serve the interests of a ruling class of people and that continues to unerringly serve those interests to this day. The logic goes like this: What “works?” Direct instruction. How do we know? Tests. Who designs the tests? The same people who have always designed the tests. What do the tests correlate with? Success in school. What does success in school correlate with? (Hint: it’s not creativity, compassion, critical thinking, scientific curiosity, artistic vision, sustainability, justice, spiritual insight, sense of humor, interpersonal skill, practical competence, or entrepreneurial success.) Success in school correlates with more school success, through a narrow band of verbal and analytical skills that are valued and measured in schools. More school success correlates with access to the elite institutions and sites of economic and political power that require school success as a gatekeeper for entry. (Oh, yeah. And it correlates with family income.)

Und sie fordert eine erweiterte Agenda für die Bildungsforschung:

outside the closed circle of Eurocentric education, there are many styles of learning that education researchers would do well to know more about –- modes of learning that could help the children who currently fail in our schools. In the many cultures where learning is consensual, non-compulsory, observational, and participatory, children acquire extraordinary levels of knowledge with no direct instruction at all. They learn through full inclusion and gradually increasing participation in adult activities, through full immersion in local ecosystems and livelihoods, through free play in multi-aged groups of children, through voluntary sharing of story, song, poetry, history. They learn through non-hierarchical collaborative forms of thinking that are rarely made possible in formal schools. They learn through a broadly focused attentional state some researchers have called “open attention” –– a state completely different from the state of narrowly focused attention demanded in schools –– which allows children to absorb detailed information through keen observation rather than direct instruction.

* * *

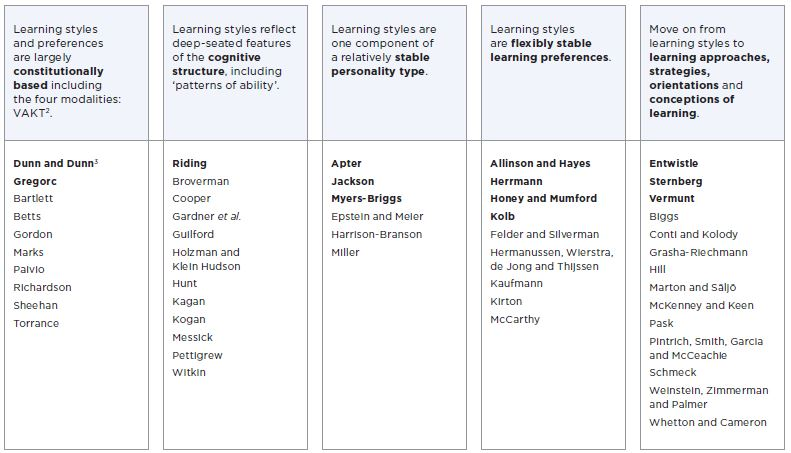

Wenn wir von dieser allgemeinen Diskussion über Fragen von Bildung und Erziehung zum Kontext der Gestaltung von (betrieblicher) Weiterbildung wechseln, so können wir festhalten, dass es sehr anspruchsvoll ist, Lernstile “dingfest” zu machen und zu operationalisieren. Studien wie die von Coffield et al. (2004) zeigen, wie breit und unterschiedlich die verschiedenen Konzeptionalisierungen von Lernstilen angelegt sind:

Diese Feststellung führt zu weiteren Fragen, die ich eingangs angeführt habe. Fragen, die auch mir in meinen Weiterbildungsmodulen häufig gestellt werden: Sollen wir als Bildungsverantwortliche Zeit und Energie für die Diagnose von Lernstilen aufwenden? Sollen wir die Gestaltung von Lernumgebungen auf unterschiedliche Typen von Lernenden bzw. Lernende mit unterschiedlichen Lernstilen ausrichten? Und wie können wir diese Anforderung mit den uns zur Verfügung stehenden Ressourcen in Einklang bringen?

Diesen Fragen geht Jane Bozarth in einem Literaturbericht nach, der kürzlich in der Reihe eLearning Guild Research publiziert wurde:

Bozarth stellt gleich zu Beginn deutlich heraus, dass es ihr nicht um die Frage geht, ob sich Lernstile nachweisen lassen:

Again, this report does not attempt to prove, or disprove, the idea of learning styles. Many voices in the field—like Furnham, above—have said it may be that we just haven’t identified the right construct for them yet. There are problems with many of the instruments, most of them relying on self-reporting of preferences that may change depending on context (…) They note that, as so much past research has been poorly conducted, there is room for research that proves them wrong. But as of now, there is a paucity of evidence showing that customizing instruction to any notion of learning style makes any difference in learning outcomes.

Bozarth fragt auch danach, warum das Thema Lernstile trotz dieser unklaren Forschungslage immer wieder auf die Agenda kommt. Sie sieht hier vor allem kommerzielle Interessen als Treiber:

Perhaps the strongest element supporting continued belief in using learning styles to design instruction is the relentless push of marketers ever-ready to sell an instrument or idea, existing against a wall of difficult-to-access and hard-to-read experimental, peer-reviewed research.

Und sie zitiert dazu aus einer anderen Studie:

These commercial entities have been a powerful force behind the propagation of learning styles instruction, a curious dynamic at odds with the reality that educational psychologists, those who are best equipped to study the concept, generally regard it with great skepticism

Bozarths Literatur- und Forschungsbericht ist auf die Frage fokussiert, ob Bildungsverantwortliche überhaupt versuchen bzw. Energie darauf verwenden sollen, Lernumgebungen für unterschiedliche Lernstile zu gestalten. Ihre Antwort auf diese Frage fällt eindeutig aus:

Can learning be improved by matching the mode of instruction to the preferred learning style of the student?

No.

At least, not according to the idea of “learning style” as we currently define it.

Wie sollen wir als Bildungsverantwortliche dann mit dem Thema “Lernstile” und “Lernpräferenzen” umgehen? Bozarth empfiehlt, das wir zunächst einmal genauer hinschauen, ob unsere Lehr-Lernumgebungen tatsächlich wie von uns angestrebt funktionieren. Darüber hinaus verweist sie auf folgende Punkte:

- mehr Zeit darauf verwenden, Informationen über unsere Lernenden / Teilnehmenden und deren Vorwissen zum Thema zu sammeln;

- mehr Zeit darauf verwenden zu überlegen, welche Bedürfnisse und Anforderungen Neulinge versus bereits erfahrene Mitarbeitende an die Gestaltung einer Lernumgebung zum fraglichen Thema haben;

- darauf achten, dass zentrale Inhalte (z.B. zentrale Wissensstrukturen) in verschiedenen Kodierungsformen vorliegen bzw. von den Lernenden bearbeitet werden können (Text UND Bild UND verbale Repräsentation bzw. Ton);

- mehr Sorgfalt darauf verwenden, die Gestaltung von Lehr-Lernumgebungen auf die Erfordernisse auszurichten, die sich aus dem Inhalt bzw. den Lernzielen ergeben – beispielsweise über praktische Übungen;

- den Lernenden in den von uns gestalteten Lernumgebungen mehr Freiraum geben und mehr Entscheidungsmöglichkeiten bei der Gestaltung ihres eigenen Lernprozesses einräumen;

- unseren eigenen Werkzeugkoffer ergänzen und mehr Variation in die von uns gestalteten Lernumgebungen bringen.

Und sie schliesst mit der folgenden Forderung:

As L&D practitioners, it behooves us to expand our own toolkits and understanding of instructional strategies that do work, to come armed with evidence and better ideas, to incorporate them into our practice, and to help others become more fluent in recognizing and creating better learning solutions.

Black, Carol (keine Angabe, vermutlich 2016): Science / Fiction. ‘Evidence-based’ education, scientific racism, & how learning styles became a myth. carolblack.org. Online verfügbar unter http://carolblack.org/science-fiction/.

Bozarth, Jane (2018): The truth about teaching to learning styles and what to do instead? eLearning Guild Research. eLearning Guild. www.elearningguild.com. Online verfügbar unter https://www.elearningguild.com/content/5730/ebook-the-truth-about-teaching-to-learning-styles-and-what-to-do-instead.

Hattie, John; Yates, Gregory C. R. (2013): Visible Learning and the Science of How We Learn. Routledge.

Beitragsbild: Photo by Edgar Castrejon on Unsplash

Schreiben Sie einen Kommentar